MCPL SIMON ARCAND

Decades of service and ownership: Reflections on the Kingston class

By CPO2 Richard Bungay,

Patrol Chief Engineer, Sea Training Atlantic

When I first stepped aboard His Majesty’s Canadian Ship (HMCS) Glace Bay as part of the commissioning crew in 1996, I never imagined I would still be tied to the Kingston class nearly three decades later. Yet here I stand, as the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) prepares to pay off the ships, reflecting on a career that has been inseparable from the life of the class itself. Over the years, I had the privilege of sailing in all five of the East Coast Kingston-class Maritime Coastal Defence Vessels (MCDVs), an experience that has shaped my service and left me with a deep sense of ownership in their legacy.

For me, the Kingston class was never simply a platform, it became a constant. From my earliest days as a roundsperson and Engineering Watchkeeper, through to my many years as Chief Engineer and later at Sea Training Atlantic Patrol, I sailed alongside shipmates who shared the same dedication, professionalism, and pride in their work. Together, we trained sailors, mentored crews, and kept these ships ready for the challenges ahead. Every success was the product of teamwork; engineers, bridge watchkeepers, supply staff, combat operators, and cooks alike, pulling together to make each ship more than the sum of its parts.

The Kingston class shaped us as much as we shaped them, and the legacy we leave behind is a shared one, carried forward by every sailor who ever signed their name into a ship’s logbook.

What began as an upgrade to the 1950s-era Gate vessels for the Naval Reserve grew into something far greater: a class of ships that quietly delivered more than ever asked of them. Over the decades, I watched them evolve into true operational assets, earning a place on the front lines of NATO and sailing in some of the most demanding environments on earth. The ships trained a generation of sailors and were constantly reinvented to deliver exceptional service to Canada, proof that ingenuity and dedication can wring greatness from even the humblest beginnings.

My own journey mirrors that transformation, and here are some notable deployments and taskings. In 1998, Glace Bay was tasked with deploying an experimental side-scan sonar to help map the wreckage of Swissair Flight 111 off Nova Scotia, supporting one of the largest recovery and investigation efforts in Canadian history. The following year, we crossed the Atlantic to take part in NATO’s Blue Game exercise, where we demonstrated minesweeping to our allies, showing that even these small vessels had real capability.

In 2000, I once again found myself in Glace Bay, this time sailing to Port Canaveral, Florida, to support former RCN Captain and astronaut Marc Garneau on his final mission into space—a moment that tied Canada’s naval and spacefaring legacies together in a way few could have imagined. Just a year later, in 2001, we were transiting off New York State when the September 11 terrorist attack took place. It was a sobering reminder that the world we served in could change in an instant, and that the RCN would have to adapt alongside it.

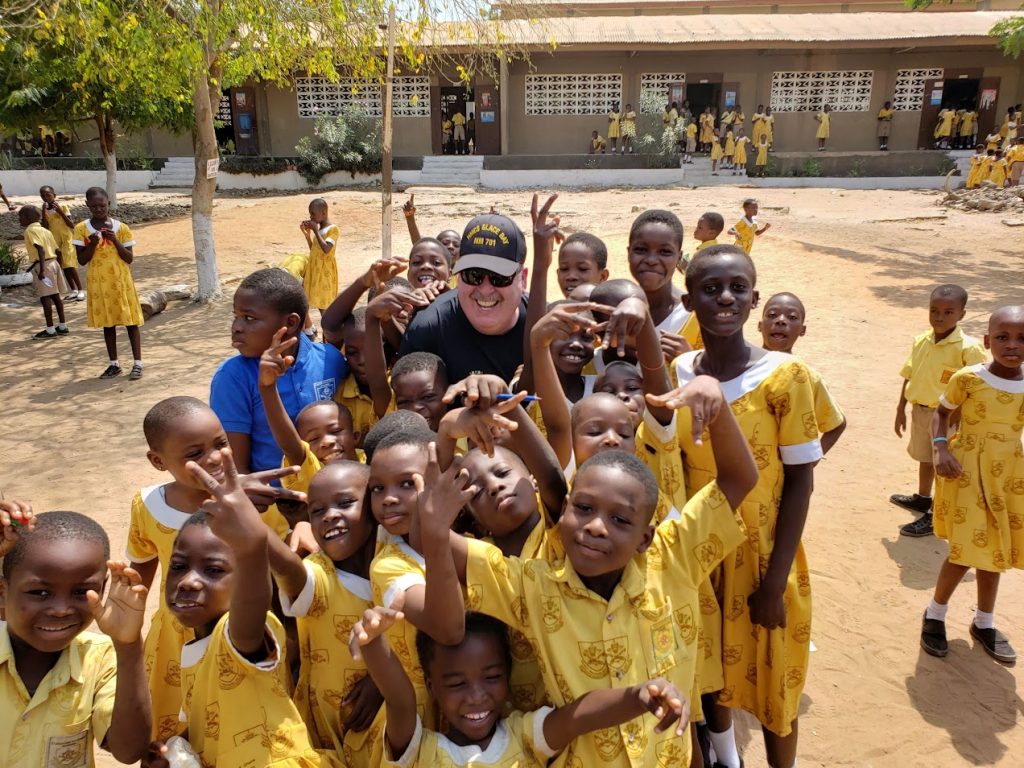

Other moments tested both the ships and those of us who sailed them. In 2005, HMCS Shawinigan rode out 14-metre seas off the Azores, a searing lesson in the unforgiving power of the Atlantic. In 2014, we pushed north in the same ship, reaching 80° latitude and proving that the Kingston class, too, could hold their own in the Arctic. Later, in 2020, I was back in HMCS Glace Bay and deployed to West Africa. That voyage left a lasting impression through the perspective gained from seeing how people live in different parts of the world. It was also a deployment marked by the new realities of operating in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, in 2022, I was again across the Atlantic, this time as part of Operation Reassurance, serving within NATO not as a training platform, but as an operational unit fully integrated with our allies. It was perhaps the most fitting testament to just how far the Kingston class had come.

The Kingston class became much more than just steel and systems; it was a source of community, a proving ground, and for many of us, a home. The ships were important, but without their crews, the teams of sailors who took ownership, worked shoulder to shoulder, and carried responsibility for every success, they would have been nothing more than hulls in the water. Those sailors were the true heart of the Kingston class, and it was their teamwork, their spirit, and their commitment that gave these ships life, purpose, and distinction.

SUBMITTED

These days, as the Kingston class begins to pay off, I am still going to sea with them, supporting their training and readiness requirements with Sea Training Patrol. I am also sailing with the Harry-DeWolf class Arctic and Offshore Patrol Vessels (AOPVs). These ships carry forward the same spirit of adaptability, teamwork, and quiet excellence that defined the Kingstons, while taking on new roles and broader missions. In many ways, they inherit not only the tasks, but also the legacy of service and the lessons forged in nearly three decades of Kingston deployments.

For me, they represent decades of service and ownership, a legacy that I will carry long after their colours are lowered. As they now prepare to leave the fleet, I can only say this: the Kingston class outlasted expectations, outperformed its critics, and outlived its doubters. They leave behind a record of quiet excellence, and those of us who called them ours will never forget the mark they made.