De gauche à droite, le Cam Brian Santarpia, commandant des FMAR(A) et de la FOIA, Jennifer Denty, Roger Litwiller et le PM 1 Tom Lizotte, premier maître de formation des FMAR(A).

JOANIE VEITCH

A view into the past: Corvette porthole donated to Naval Museum of Halifax

By Joanie Veitch,

Trident Staff

A porthole from the wreck of HMCS Trentonian, the last corvette lost in the Battle of the Atlantic, was presented to the Naval Museum of Halifax on December 8.

Author and naval historian Roger Litwiller made the donation of the porthole, which is one of two that were recovered from the wreck recently by a dive team from the United Kingdom. A small gathering to mark the significance of the donation included Jennifer Denty, museum director, Kyle Houghton, a university student who is cataloging the museum’s artwork, Rear-Admiral Brian Santarpia, Commander Maritime Forces Atlantic (MARLANT) and Joint Task Force Atlantic (JTFA), and CPO1 Tom Lizotte, Formation Chief of MARLANT.

“We’re thrilled to be able to add this to the collection and humbled to be thought of as the proper caretaker for the artifact,” said Denty.

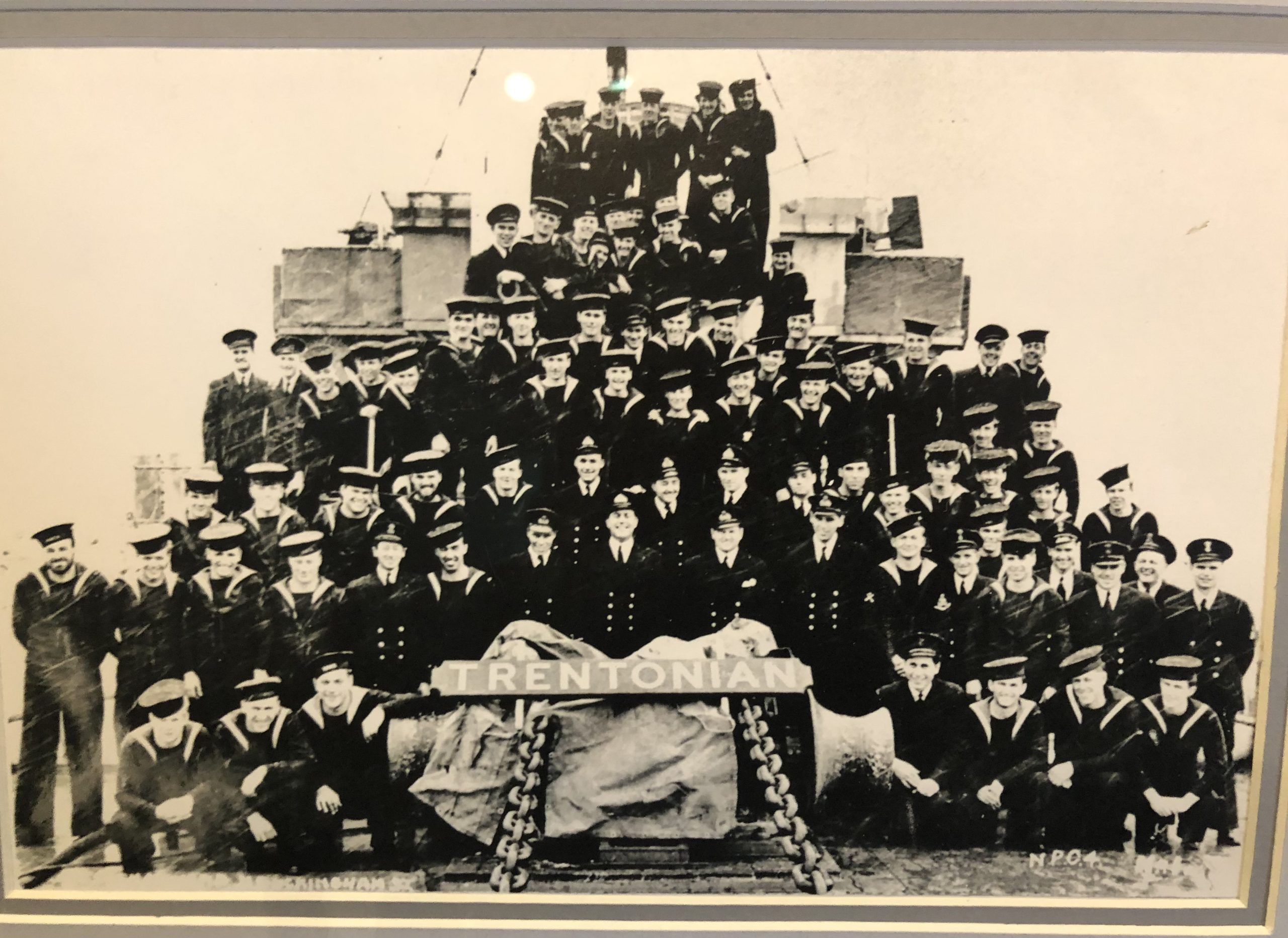

Speaking to the small group assembled around a temporary display table on the second floor of the museum, along with a framed print of Trentonian and a photograph of the ship’s company, Litwiller recounted the chronology of how the portholes came into his possession.

The story began with an email he received in May 2021. One of the members of the dive team that took the portholes from the wreck had done some research online and found Litwiller’s website on Canadian naval history; Litwiller has also written a book about HMCS Trentonian, White Ensign Flying, published by Dundurn Press in 2014.

“I got this email from the fellow saying ‘I’m a diver here in the UK. We did a dive on Trentonian in the spring and, despite my warnings to the crew, two of our club members… came up with portholes from the wreck’. He managed to talk them into handing them over,” Litwiller said.

Gesturing to the bent and broken porthole, Litwiller said the diver told Litwiller he had two of the ship’s portholes — one that “was kind of busted up” and another in “excellent” condition.

After further questioning, Litwiller said he determined that the damaged one came from the “starboard aft” — the area of Trentonian that had been torpedoed.

“The damage to this one was from the torpedo, from the explosion… the force to wrench it like this was phenomenal,” he said. “That tells a whole story all on it’s own.”

The story of HMCS Trentonian

NAVAL MUSEUM OF HALIFAX/MUSÉE NAVAL D’HALIFAX

Following the ship’s commissioning in Kingston, ON, on December 1, 1943, HMCS Trentonian was fitted out in Nova Scotia, and went through work-ups before being assigned to Western Approaches Command in March 1944 to escort convoys across the North Atlantic to the west of Ireland and Great Britain.

On February 22, 1945, while escorting a convoy across the English Channel, Trentonian was torpedoed near Falmouth, killing six sailors and wounding 14 more. The torpedo struck the back right side of the ship, near where the life rafts were stored, said Litwiller.

One of the men killed was John McCormack, a 19-year-old stoker from Belleville, ON, who had transferred to the ship just a few weeks before the torpedo hit. Formerly a sea cadet, McCormack was at Kingston when Trentonian was commissioned and was thought to be the youngest sailor on the ship.

“He had just done the Christmas exchange with the CO (Commanding Officer). His was one of the stories that haunted me when I was writing the book. Every one of the survivors I interviewed talked about John McCormack and how he was just a kid.”

McCormack wasn’t actually the youngest on board the ship, however, as Litwiller discovered when doing interviews for his book. “Bill Shields was the youngest. He had lied about his age to join the Navy, so that Christmas when John McCormack was given the honour of youngest sailor, Bill was really the youngest, but couldn’t say anything.”

William Shields died at age 93 in Oakville, ON on June 6, 2020.

Protecting historical shipwrecks

The waters off the coast of Britain and Ireland are home to thousands of shipwrecks and considered war graves for the sailors who went down with the ships. While the UK has enacted laws to protect wrecks of historical significance — specifying that artifacts must not be disturbed or removed — Canada has yet to enact similar protections.

“Pilfering and looting of our wrecks is carrying on all the time. An artifact like this has such huge historic significance… I’m just glad they contacted me. My biggest fear with artifacts like this is that they end up as a lawn ornament in somebody’s garden or sitting in a scrap heap to be melted down.”

Litwiller is donating the second porthole to the Marine Museum of the Great Lakes at Kingston, which recently moved back to the Kingston Dry dock property, a National Historic Site and former location of the Kingston Shipyards Co, where HMCS Trentonian was built.

Un regard vers le passé : Don d’un hublot de corvette au Musée naval d’Halifax

Par Joanie Veitch,

Personnel du Trident

Un hublot provenant de l’épave du NCSM Trentonian, la dernière corvette perdue dans la bataille de l’Atlantique, a été remis au Musée naval d’Halifax le 8 décembre.

L’auteur et historien de la Marine Roger Litwiller a fait don du hublot, l’un des deux qui ont été récupérés de l’épave récemment par une équipe de plongée du Royaume-Uni. Jennifer Denty, directrice du musée, Kyle Houghton, étudiant universitaire qui catalogue les œuvres d’art du musée, le contre-amiral Brian Santarpia, commandant des Forces maritimes de l’Atlantique (FMAR(A)) et de la Force opérationnelle interarmées (Atlantique) (FOIA), et le premier maître de 1re classe Tom Lizotte, premier maître de formation des FMAR(A), ont pris part à un petit rassemblement pour souligner l’importance de ce don.

« Nous sommes ravis de pouvoir ajouter cet objet à la collection et nous sommes honorés d’être considérés comme le gardien approprié de l’artéfact », a déclaré Mme Denty.

The portholes were recovered by a UK dive team before passed over to naval author and historian Roger Litwiller.

JOANIE VEITCH

Alors qu’il s’adressait au petit groupe rassemblé autour d’une table d’exposition temporaire au deuxième étage du musée, ainsi que d’une image encadrée du Trentonian et d’une photographie de l’équipage du navire, M. Litwiller a raconté la chronologie de la façon dont les hublots sont entrés en sa possession.

L’histoire commence par un courriel qu’il a reçu en mai 2021. L’un des membres de l’équipe de plongée qui a prélevé les hublots de l’épave a fait des recherches en ligne et trouvé le site Web de M. Litwiller sur l’histoire de la Marine canadienne. M. Litwiller a également écrit un livre sur le NCSM Trentonian, White Ensign Flying, publié par Dundurn Press en 2014.

« J’ai reçu un courriel de cet homme qui m’a dit : ‘Je suis plongeur ici au Royaume-Uni. Nous avons fait une plongée sur le Trentonian au printemps et, malgré mes avertissements à l’équipage, deux des membres de notre club… sont remontés avec des hublots de l’épaveʼ. Il a réussi à les convaincre de les remettre », a déclaré M. Litwiller.

En montrant le hublot tordu et cassé, M. Litwiller a déclaré que le plongeur lui avait dit qu’il avait deux hublots du navire — un qui était « en quelque sorte abîmé » et un autre en « excellent » état.

Après d’autres questions, M. Litwiller a déclaré qu’il avait déterminé que le hublot endommagé provenait de l’« arrière tribord » — la zone du Trentonian qui a été torpillée.

« Les dommages subis par celui-ci proviennent de la torpille, de l’explosion… la force qui l’a arraché comme cela était phénoménale, a-t-il dit. Cela raconte toute une histoire à lui seul. »

L’histoire du NCSM Trentonian

Après la mise en service du navire à Kingston en Ontario le 1er décembre 1943, le NCSM Trentonian a été équipé en Nouvelle-Écosse et a fait sa croisière d’endurance avant d’être affecté au Commandement des approches occidentales en mars 1944 pour escorter des convois qui traversaient l’Atlantique Nord jusqu’à l’ouest de l’Irlande et de la Grande-Bretagne.

Le 22 février 1945, alors qu’il escortait un convoi dans la Manche, le Trentonian a été torpillé près de Falmouth, ce qui a tué six marins et a blessé 14 autres. La torpille a frappé le côté arrière droit du navire, près de l’endroit où étaient entreposés les radeaux de sauvetage, a déclaré M. Litwiller.

L’un des hommes tués était John McCormack, un chauffeur de 19 ans originaire de Belleville, en Ontario, qui avait été transféré sur le navire quelques semaines seulement avant que la torpille ne frappe. Ancien cadet de la Marine, M. McCormack était à Kingston lorsque le Trentonian a été mis en service et on pensait qu’il était le plus jeune marin du navire.

« Il venait de faire l’échange de Noël avec le cmdt (commandant). Son histoire est l’une de celles qui m’ont hanté lorsque j’ai écrit le livre. Tous les survivants que j’ai passés en entrevue ont parlé de John McCormack et du fait qu’il n’était qu’un enfant. »

John McCormack n’était cependant pas le plus jeune à bord du navire, comme M. Litwiller l’a découvert en réalisant des entrevues pour son livre. « Bill Shields était le plus jeune. Il avait menti sur son âge pour s’enrôler dans la Marine, si bien que ce Noël, lorsque John McCormack a reçu l’honneur d’être le plus jeune marin, Bill était en réalité le plus jeune, mais ne pouvait rien dire. »

William Shields est décédé à l’âge de 93 ans à Oakville, en Ontario, le 6 juin 2020.

Protéger les épaves historiques

Les eaux au large des côtes britanniques et irlandaises abritent des milliers d’épaves et sont considérées comme des sépultures de guerre pour les marins qui ont sombré avec les navires. Le Royaume-Uni a adopté des lois pour protéger les épaves d’importance historique — en précisant que les artéfacts ne doivent pas être dérangés ou enlevés — le Canada n’a pas encore adopté de protections similaires.

« Le chapardage et le pillage de nos épaves se poursuivent sans cesse. Un artéfact comme celui-ci a une telle importance historique énorme… Je suis simplement heureux qu’ils aient communiqué avec moi. Ma plus grande crainte avec des artéfacts comme celui-ci est qu’ils finissent comme décorations dans le jardin de quelqu’un ou qu’ils se retrouvent dans un tas de ferraille pour être fondus. »M. Litwiller fait don du deuxième hublot au Musée maritime des Grands Lacs à Kingston, qui a récemment de nouveau emménagé sur la propriété de la cale sèche de Kingston, un lieu historique national et l’ancien emplacement de la Kingston Shipyards Co, où le NCSM Trentonian a été construit.