DND

When war came to Newfoundland: The sinking of SS Caribou

By CPO1 (Ret’d) Pat Devenish,

Canadian Naval Memorial Trust

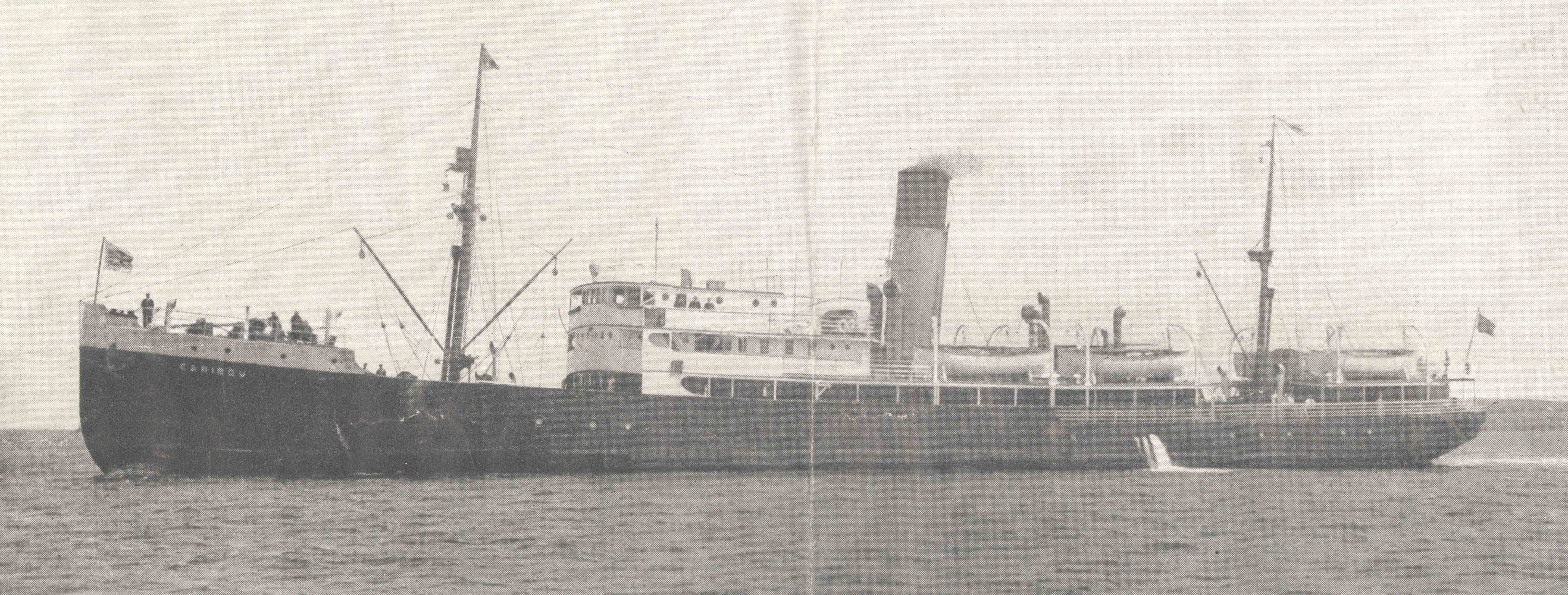

On an early morning in May of 1986, the new ferry Caribou, on her maiden voyage between North Sydney in Cape Breton and Port-aux-Basques, Newfoundland, slows to a spot in the Cabot Strait south of her Newfoundland destination. It was at this spot in October of 1942 that the first Caribou, a Newfoundland registered passenger ferry plying the waters between North Sydney and Port-aux-Basques, as it had been doing for the previous 17 years, became a victim of war.

Displacing 2200 tons, 265 feet long and loaded with 450 tons of cargo, 191 passengers and a crew of 46, Caribou was owned by the government-run Newfoundland Railway. She was an institution to the people of Newfoundland and as Britain’s oldest colony, she reflected a common pride in Newfoundland’s contribution in this, now the third year of war.

Although denoted as a passenger ship, Caribou became a target in a game called war; a game where rules exist but they do not exist. To a U-boat Captain and crew on a chilly, windy autumn evening, a vessel not flying a German ensign was the enemy. A culmination of events leading up to the evening of October 13, 1942 and the early morning hours of the following day brought home to the people of Newfoundland the harsh realities of war.

By 8:00 p.m. on the evening of October 13, 1942, all passengers and cargo are on board Caribou as her Captain, Ben Taverner, a native Newfoundlander and his crew, also composed primarily of Newfoundlanders, prepare to put their ship to sea. Of the 191 passengers, 118 are in uniform enroute to their destinations of duty. Of the remaining passengers, most are somehow involved in the war effort, including wives and children of serving members. As this is war, HMCS Grandmere, a ‘Bangor’ class minesweeper is tasked with providing escort duties. As Grandmere slips her moorings and proceeds to North Sydney’s harbour mouth to conduct a customary sonar sweep, the crew of Caribou prepares their human cargo for the normally serene 96-mile transit to Port-Aux-Basques.

Since the United States’ entry into the war following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, German submarines have ventured daringly close to land to conduct attacks on Allied merchant shipping all along the eastern seaboard of the U.S., Canada and Newfoundland. In the five months leading up to October 1942, U-boats sunk 19 vessels either in or very close to the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River, often within sight of the residents of the coastal communities along the shores. Although closed to ocean shipping, the Gulf area remained open for vessel transits between the Maritime Provinces and Newfoundland including passenger ferries.

Due to overwhelming commitments for Trans-Atlantic escort duties, the Canadian Navy is forced to relegate its smaller warships for escort duties within Canadian waters. It is for this reason that a minesweeper is tasked with this escort duty. Unfortunately, the Canadian Navy is almost pathetically unprepared for war because of years of neglect since World War I. The Captain and crew of Grandmere prepare for their escort duties after returning to North Sydney just 2 days after conducting depth charge attacks on a suspected submarine in the Cabot Strait which has sunk the British merchantman Waterton.

As in any tight knit colony, it is no surprise that many of the crew on Caribou are from common families. Two of Captain Taverner’s sons are his Third and First Mates and there are also eight pairs of brothers. Most are from either Port-Aux-Basques or nearby from the tiny community of Channel. Although this seems to overexpose one small community to war, there is a pride in Caribou’s crew unmatched. Recently refitted with new propulsion and communication equipment as well as improved life saving gear, Caribou and the people who work her are as prepared for the eventuality of war as they can be.

As the evening of October 13, 1942 settles in, the Captain and the crew of U-69 welcome the solitude and safety of darkness as they carry on what has been a fairly successful patrol. For the last month, ranging from the Grand Banks off Newfoundland to just south of Baltimore, Maryland, they have ventured deeper into the Gulf of St. Lawrence than any other German submarine has gone to date. Just 4 days prior, the Finnish merchantman Carolus is sunk less than 200 miles downstream from Quebec City. This night, the Captain of U-69 has chosen the Cabot Strait to surface in and in the words of his log “…steaming to and fro, cruising…”.

On board Grandmere, Captain and crew prepare for, what has been in the past, a relatively uneventful transit. In her ten months in commission, most of her career has been spent on coastal escort duty although the crew is well trained and primed for any eventuality, they have never seen, let alone fought, an enemy submarine.

By 8:30 in the evening, passing through the submarine nets of Sydney Harbour, Caribou falls in behind Grandmere as Grandmere sounds the harbour approaches for enemy submarines. When complete, Grandmere falls in astern of Caribou to commence the transit. Although Grandmere establishes a zig-zag pattern immediately to cover as large an area as possible with her asdic, it is not deemed necessary at this point in the war for single escorted vessels to do the same. As the pair head almost due north to a point off Cape Breton Island’s northern tip, passengers and crew on board Caribou are unusually fidgety on this very dark, moonless night. Records indicate that even in the dark, Caribou was visible out to 2500 yards and displaying very poor “smoke discipline”.

Wartime doctrine to the Captains of both vessels also present problems. To the Caribou she must sail at night. Every crewmember knows that the chances of being attacked in broad daylight by a submarine are slim at best. As well, even if there were an attack, the chances of finding survivors improve greatly due entirely to the light of day. These, however are the rules as set forth by the Naval Commander at the Western Approaches Headquarters in Liverpool, England. An even more unpleasant potential task faces the Captain of Grandmere. His rules state that if attacked by an enemy submarine, he must press the attack until there seems little chance of the submarine’s surviving. This may, and actually did on several occasions during World War II, mean that an escort vessel would have to sail amongst survivors dropping depth charges.

To the north, southwest of Port-aux-Basques, U-69 sits on the surface, batteries charged, crew well rested and prepared for a possible target that may stray into the area. Little do they know that one is, as they unknowingly prepare for the eventuality.

By 3:30 a.m. on the morning of the 14th, Caribou and her escort are 25 miles south of Port-aux-Basques as both crews prepare for their arrival in Port-aux-Basques. As the story is later told, twice Captain Taverners ventures to Caribou’s stern and twice, he fails to see Grandmere, but as records indicate, she is there. U-69’s log indicates, with her initial sighting at 3:21, two ships; a larger one ahead and an escort astern: Grandmere. As U-69 approaches from amidships of Caribou, Grandmere is unable to detect as the sounds of Caribou’s own propellors drown out everything else to the hydrophone operators on Grandmere. Also, as she is low in the water and it is a moonless night, U-69 is not detectable by lookouts on either ship.

Just before 3:25, a huge flash fills the sky as a torpedo fired at near point blank range from U-69 strikes Caribou midships just forward of the funnel. In the fiery light of the explosion, the surfaced submarine is finally sighted by the lookouts on Grandmere and as the distance is relatively short, Grandmere heads straight for the submarine in an attempt to ram. The torpedo has entered near Caribou’s machinery room and within seconds, she is dead in the water and settling by the stern.

By this time, the range between the submarine and Grandmere is down to 350 yards and Grandmere’s Captain has full speed rung on to close the distance. The submarine begins settling as it commences a crash dive, forcing Grandmere to alter course to the submarine’s projected position so a depth charge attack may be initiated.

Of Caribou’s six lifeboats, two are destroyed by the explosion from the torpedo. Two more are rendered useless when in the panic of the moment, they are cut loose from the davits and fall below to the sea. Only two boats on the port side make it into the water and they are overcrowded to the point of nearly sinking. Also in the water are roughly a dozen rafts and carley floats and passengers and crew still attempt to free up more from Caribou’s upper deck. In the four minutes of terror and panic from the time of the torpedo strike to Caribou’s demise as she sinks below the waves about two-thirds of the passengers and crew safely make it off.

As Caribou slides to a watery grave 1500 feet below, Grandmere continues a gradual turn to starboard arriving at a spot just ahead of the swirling wake of U-69’s dive to drop a diamond pattern of depth charges. However, by this time, U-69 is well below the depth charge’s settings of 150 feet and the submarine escapes to the safety of the depths.

Meanwhile in the waters around the location of the sinking, people are struggling and grappling for a position in a life raft or boat and more people drown or succumb to hypothermia in the confusion as one of the life rafts repeatedly capsizes. Immediately below the survivors lurks U-69, her Captain secure in the belief that the Captain of the Grandmere will not depth charge this area. His gamble pays off as the submarine’’ logs report distant explosions indicating that Grandmere is no longer detecting him. Also, due to the turmoil in the water, Grandmere’s asdic is rendered virtually useless.

By 5:30 a.m., as the morning light begins to splinter across the sky, Grandmere’s Captain makes a decision to abandon the attack on the submarine and concentrate on the survivors from the Caribou. He has followed the Navy’s rules to hunt a submarine until “there is little chance the enemy is still around”. It has now been two hours since the survivors entered the water and fear spreads through Grandmere’s crew as they suspect there will be no one found alive. Even by 6:30 a.m. with the assistance of a Canso flying boat out of Sydney, no survivors are picked up and the fear in Grandmere’s crew turns to dread. Finally around 7 a.m., survivors are sighted and the crew of Grandmere is rejuvenated. There is unselfish heroism on the part of many of Grandmere’s crew as they jump into the icy waters themselves to rescue survivors and by 9:40 a.m., four other Naval vessels and another aircraft are in the vicinity. With every available space filled with survivors, Grandmere turns and heads for Sydney with 106 survivors, but by the time their radio message is sent off, two more die.

Of the 240 passengers and crew aboard Caribou when she slipped the safety of Sydney harbour, there are just 104 survivors. Of her 46 crew, just 15 are alive to recount the story. These 15 do not include Captain Taverners and his two sons, nor five of the eight pairs of brothers.

In the aftermath, a publicly demanded inquiry found no fault with either the actions of Caribou’s crew nor with her life saving equipment. Grandmere too escaped ridicule as she did what was expected “given the circumstances”. Quietly and quickly however the Navy moved to eliminate night crossings for coastal traffic and RAdm Leonard Murray, Commanding Officer Atlantic Coast, informed the Newfoundland Railway: “…in confidence that the advantages of sailing at night are now outweighed by the opportunities for rescue in day time operations”.

U-69 surfaced the following night only to find aircraft and surface craft still searching the area. Quietly but deliberately, U-69’s Captain made the decision to depart the area and get as far away as possible by day break. U-69 was later sunk in the mid-Atlantic with the loss of all hands.

Conclusion

The story of the Caribou is one which touched the hearts of all Newfoundlanders at the time. Even today, mention of it sparks memories and stories passed on seemingly so long ago by older relatives. For more information on this story, I highly recommend Douglas How’s book “Night of the Caribou” or if you feel you don’t have time to read the book, Reader’s Digest has the condensed version in it’s Book Section of the October 1992 edition.