NAVAL MUSEUM OF HALIFAX

HMCS Athabaskan: We fight as one

By CPO1 (Ret’d) Patrick Devenish,

Canadian Naval Memorial Trust

This is the first of a two-part series on the 1944 sinking of HMCS Athabaskan

In April of 1974, a group of survivors, family and friends of the veteran Second World War Tribal Class destroyer HMCS Athabaskan gathered to honour the Athabaskans who did not return from her final patrol. Beginning at England’s National Naval War Museum, the group commenced retracing the steps of that fateful morning. Sailing from Plymouth, HMCS Athabaskan III stopped at the spot 48* 43’N. 04*32’W off the Brittany coast to conduct what has been hailed as one of the most moving memorials to Canada’s war dead. Once in Brest, the Canadiens were welcomed with open arms and the group broke up to visit cemeteries in the surrounding communities where 91 Athabaskan crewmembers were lovingly laid to rest in the days and weeks following her final action. The local inhabitants to this day still maintain the sites in Brest, Brignogan-Plages, Cleden-Cap-Sizun, Ile-de-Batz, Landeda, Plouescat, Plougasnou, Pornic and Sibril.

In a very condensed form, this is the story leading up to and the aftermath of the events that transpired in the early hours of April 29, 1944. It is a story of harrowing events, untold heroism and shear guts and determination. In order not to offend any family members or survivors, names of personnel are left out with the exception of ship’s Commanding Officers. To experience this story more in depth, the book Unlucky Lady, compiled and written by Len Burrow and Emile Beaudoin, offers a firsthand account that puts the reader into the story. A touching listing at the book’s end accounts for the whereabouts of each member of the crew following that fateful morning.

Introduction

Canada’s stature as a major naval power at the end of the Second World War was quite different from the predicament that existed when the war erupted in September 1939. From a force of 13 vessels and slightly more than 3000 regular and reserve force members, the Royal Canadian Navy grew to a force of 500 vessels and almost 100,000 officers and NCMs by the end of hostilities in 1945, being the 3rd largest Navy of all Allied nations.

After the fall of France in the spring of 1940, Canada’s priority became maintaining the convoy route to Europe. For this, antiquated vessels were hurriedly acquired and updated from Britain and the United States. Prewar planning also meant that by 1943, the Royal Canadian Navy had four destroyers of the British Tribal class in her arsenal: HMC Ships Iroquois, Athabaskan, Haida and Huron. These ships were built in England. Later, four Canadian-built ships, Micmac, Nootka, Cayuga and Athabaskan II arrived too late to see service in the Second World War. Britain’s Royal Navy had 16 Tribals in service. These were the elite of their flotillas and their degree of strength is demonstrated by the fact that just four would still be afloat by war’s end.

The Beginning(s)

The steel for Canada’s first two Tribals was cut in late 1940 with construction of the first, Iroquois and the second, Athabaskan, well underway by the spring of 1941. Late in April 1941 the Luftwaffe bombed the shipyards where Iroquois and Athabaskan were being constructed at Vickers-Armstrong, High Walker Yard, Newcastle-on-the Tyne. Iroquois, which was destined to be Canada’s first Tribal was severely damaged in the slips while alongside, Athabaskan was relatively unscathed. After much discussion, it was decided to rename Athabaskan as Iroquois and Iroquois as Athabaskan so that Iroquois could launch first.

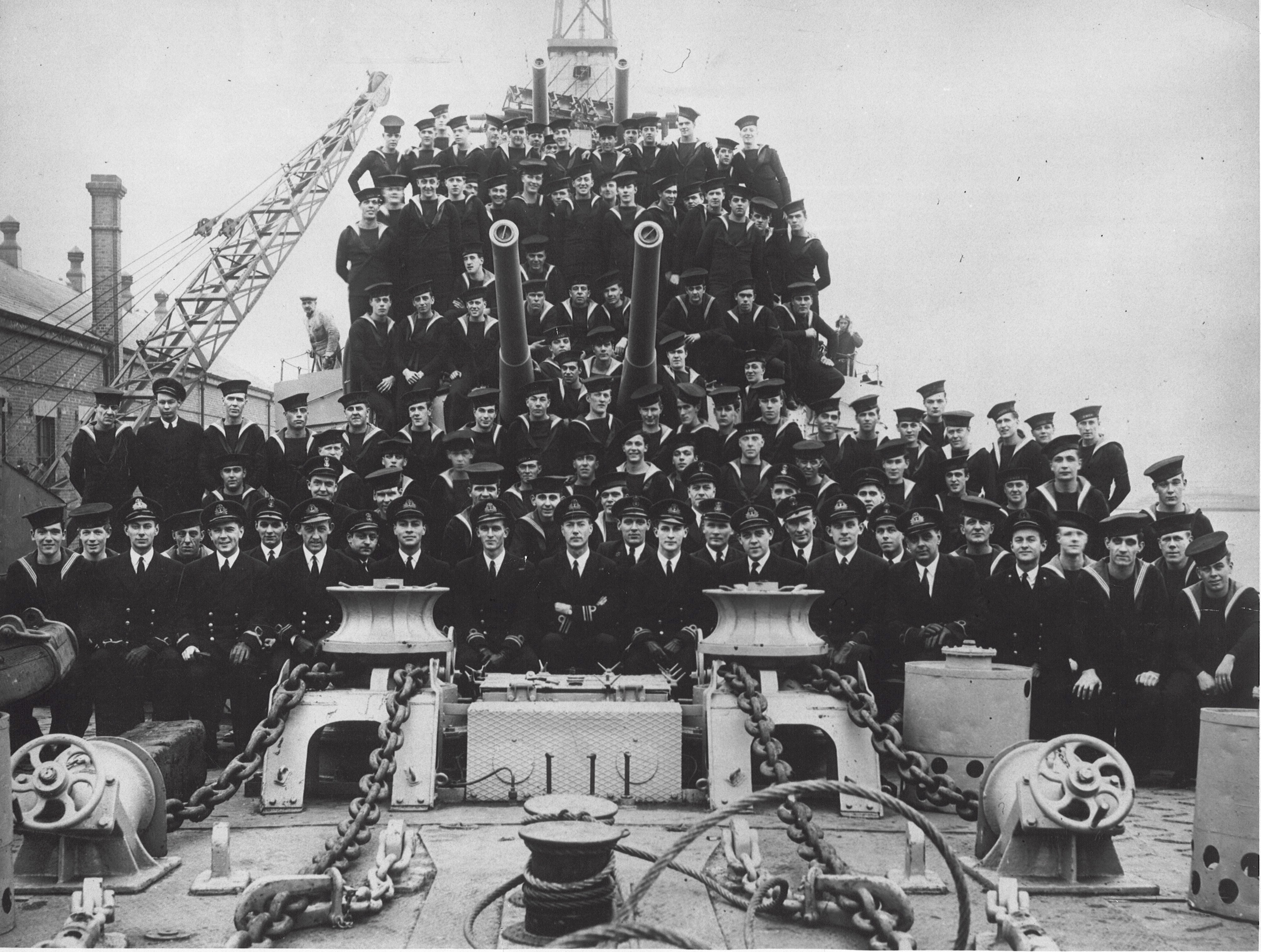

The new Athabaskan, damage repaired and trials conducted, slipped into the River Tyne to be towed to the fitting out basin on November 18, 1941. On February 3rd, 1943, Canada’s second Tribal was finally commissioned to the shrill of a bos’n’s call: “Carry on”, with Cdr George R. Miles as Athabaskan’s first Commanding Officer.

Almost immediately, trials and a crew work-up began with the ship suffering her first damage in a collision when berthing alongside an oiler. In her first patrol off Scotland’s Faeroe Islands, severe weather caused the fo’cs’le plating to separate allowing seawater in. Finally on return from a patrol to Spitzbergan, she collided with the cable from a gate vessel in Scapa Flow, tearing a slice in her bow. It was now summer and although the ship had suffered damage requiring a docking, the enemy had not yet been engaged.

By the end of July 1943 after being repaired, Athabaskan once again was put to sea with Force W patrolling the Bay of Biscay. It was on one of these patrols that Athabaskan’s crew got a rude awakening from the enemy in the form of a glider bomb. One of Hitler’s wonder weapons, one of the first generation smart bombs struck the ship at the junction of B gun deck and the wheelhouse. Damage was severe enough for Athabaskan to be pulled out of action and after burying her dead at sea, the ship turned north arriving in Plymouth on the July 30. It was during this brief lull while the ship was repaired, radar upgraded and more anti-aircraft punch added that LCdr John H. Stubbs assumed command.

By November, Athabaskan was once again a fighting ship and little time was lost assigning her to escort duties with a convoy heading to Kola Inlet, Russia. After a relatively uneventful trip, Athabaskan began the New Year of 1944 escorting the battleship King George V with Churchill himself aboard from Gibraltar to Plymouth.

Early in 1944, plans for the establishment of a western front in France were well under way. Before this could be successful however, it was necessary to clear the English Channel of all German shipping. German convoy interception patrols, codenamed TUNNEL began the end of January and carried on through February and March. Into April, much of Royal Navy Task Force 26, which now comprised the destroyers Athabaskan, Haida and Huron as well as HMS Ashanti and the light cruiser HMS Black Prince carried out nightly raids on enemy shipping. On top of this, the Force also provided a screen for mine layers, code named HOSTILE. On one such mission on April 26, the German destroyer T-29 was sunk and Ashanti and Huron damaged after colliding with T-29 and two other German destroyers. The stage was now set and two nights later Haida and Athabaskan sailed into the English Channel alone; it became painfully clear that the brunt of responsibility would fall on the crews of these two ships.

The Battle

At 1500 on April 28, both ships reverted to two hours steaming notice finally slipping at 2000 for another HOSTILE mission supporting minelayers. As Haida pulled away, Athabaskan’s mascot, a cat named Ginger, attempted to jump across to Haida, causing a superstitious stir among some of Athabaskan’s crew. By 0200 on April 29, both ships had arrived at their designated position and began patrolling at 16 knots. Earlier in the evening, reports received from Plymouth revealed that French underground forces observed the departure from St. Malo of the German destroyers T-24 and T-29, the survivors of the action two nights previous. Just before 0300, radar on Athabaskan and Haida picked up the two enemy vessels and just after 0400, Haida, which was slightly closer, fired a starshell from 7,200 yards. Two minutes later, lookouts on both Tribals observed the two German destroyers heading west at high speed; the chase was on and as the distance between the ships closed to 7,000 yards, both Athabaskan and Haida fired all guns. As T-24 and T-29 turned to open the distance, they too fired all guns as well as a spread of torpedoes. As both groups of ships continued to fire on one another, Athabaskan’s radar operator reported two high-speed contacts on the ship’s starboard quarter. As T-24 and T-29 were to port, these were new contacts and by their station keeping and speed it became obvious that they were German E-boats. Just as Athabaskan came out of a hard turn, a torpedo struck her starboard stern. Both X and Y batteries were immediately destroyed and their crews decimated as the explosion shuddered through Athabaskan’s length. With major fires aft, steering jammed and propulsion lost, Athabaskan began to slow finally stopping as her stern settled in the water. On Haida, it was decided to maintain the pursuit of the two fleeing enemy destroyers and as she departed the area, she trailed a smokescreen in an attempt to hide the glow of flames from Athabaskan’s stern.

As Athabaskan’s crew struggled to save their ship in a now dispersing smoke screen, ammunition from the after magazines began exploding. To make matters worse, the ship drifted toward the French coast and now came under fire from German shore batteries. The reality of the situation became apparent as the Captain ordered his crew to prepare to Abandon Ship. Just after 0420, only 10 minutes after the first torpedo, a second one struck from the starboard hitting just aft of the bridge. Within seconds, the after magazines and fuel tanks exploded sending shrapnel, steam, piping and flames high into the air. Haida, now five miles to the east, was witness to the explosion astern of her and her Captain, LCdr DeWolf decided to turn back toward Athabaskan. The ship was now ablaze from #1 Boiler Room to her stern and LCdr Stubbs ordered Abandon Ship. By this point, many men were already in the water having been blown over the side from one of the many explosions. At 0428, all was suddenly quiet as the last protesting screams were uttered by the sinking ship and it slid nearly perpendicular, stern first to its eternal grave. LCdr DeWolf radioed Plymouth HQ: “Athabaskan has blown up.”

To be continued in the May 4 edition of Trident.