DRDC(A)

The Bedford Range turns 80

By Cdr Brian May,

Associate Centre Director and Detachment Commander,

Military Support Unit Atlantic, DRDC

In the opening days of the Second World War, German aircraft began laying magnetic sea mines in the harbours of Great Britain to create a shipping blockade. The magnetic mine had been used previously in the First World War, but their now-easy deployment from aircraft created new operational challenges for the Allied Nations.

Ships’ vulnerability to this undersea threat lie in the fact that when work is done to the metal structure of a ship in the ever-present earth’s magnetic field, the ship itself becomes a magnet of significant size and strength. As the ship moves through the water, it temporarily changes the earth’s magnetic field in its immediate vicinity and this change can be detected by the trigger mechanism of the mine, initiating an explosion. In theory, it is easy to protect a ship from these mines by neutralizing, or at least greatly reducing, its magnetism.

COURTESY OF DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY

The process of reducing a ship’s magnetism is called degaussing; it’s accomplished by passing an electrical current through specifically placed coiled cables within the ship to create an electromagnet of opposite polarity to that of the ship. The challenge is, however, that each ship is a magnet of a different size, shape and polarity, and so its specific signature needs to be measured for the degaussing (DG) system to operate to maximum effect.

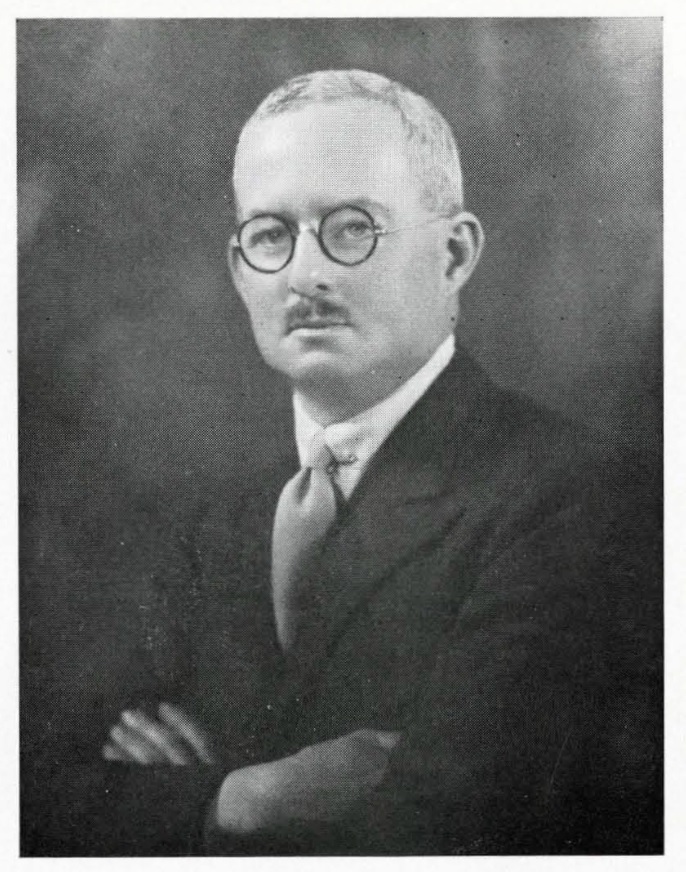

In the early days of the Second World War, the Royal Canadian Navy accepted the responsibility to degauss ships sailing from Canada to Europe. Canadian scientists had worked closely with those of the Entente Powers during the First World War to combat submarines and mines, but in September of 1939, Defence Science still had no formal place within the activities of the Canadian Government. In February of 1940, the Naval Staff approached two professors at Dalhousie University, Dr. G.H. Henderson (1892-1949) and Dr. J.H.L. Johnstone (1891-1973), to develop degaussing techniques. What information that was available at the time, arrived in “MOST SECRET” messages from the Admiralty, providing the estimated sensitivity of the enemy’s mines. Early experimental work was conducted by the staff of the Defensively Equipped Merchant Ship Section of HMC Dockyard in Halifax, and the Nova Scotia Light and Power Company installed the DG coils and necessary electrical generating equipment in the ships.

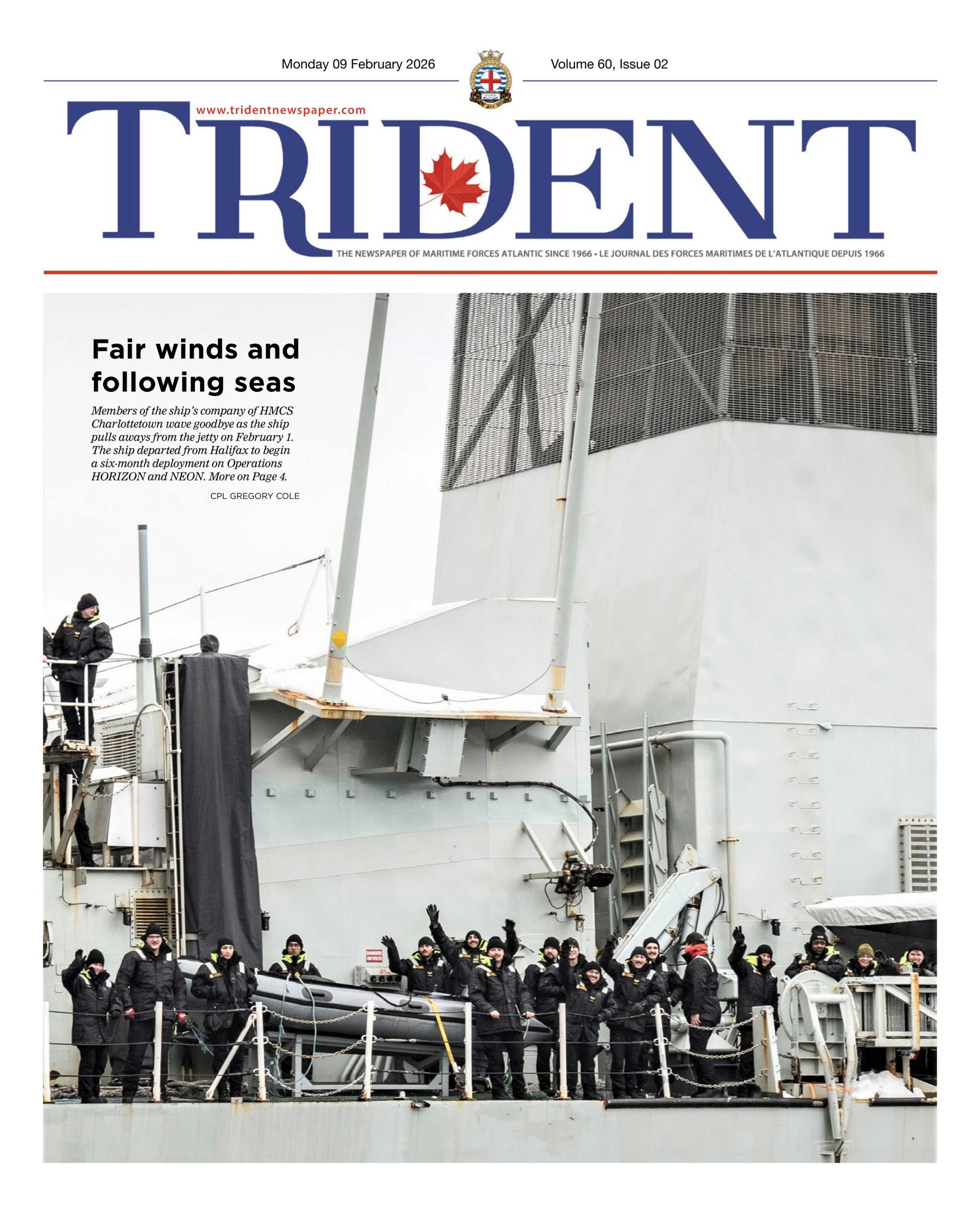

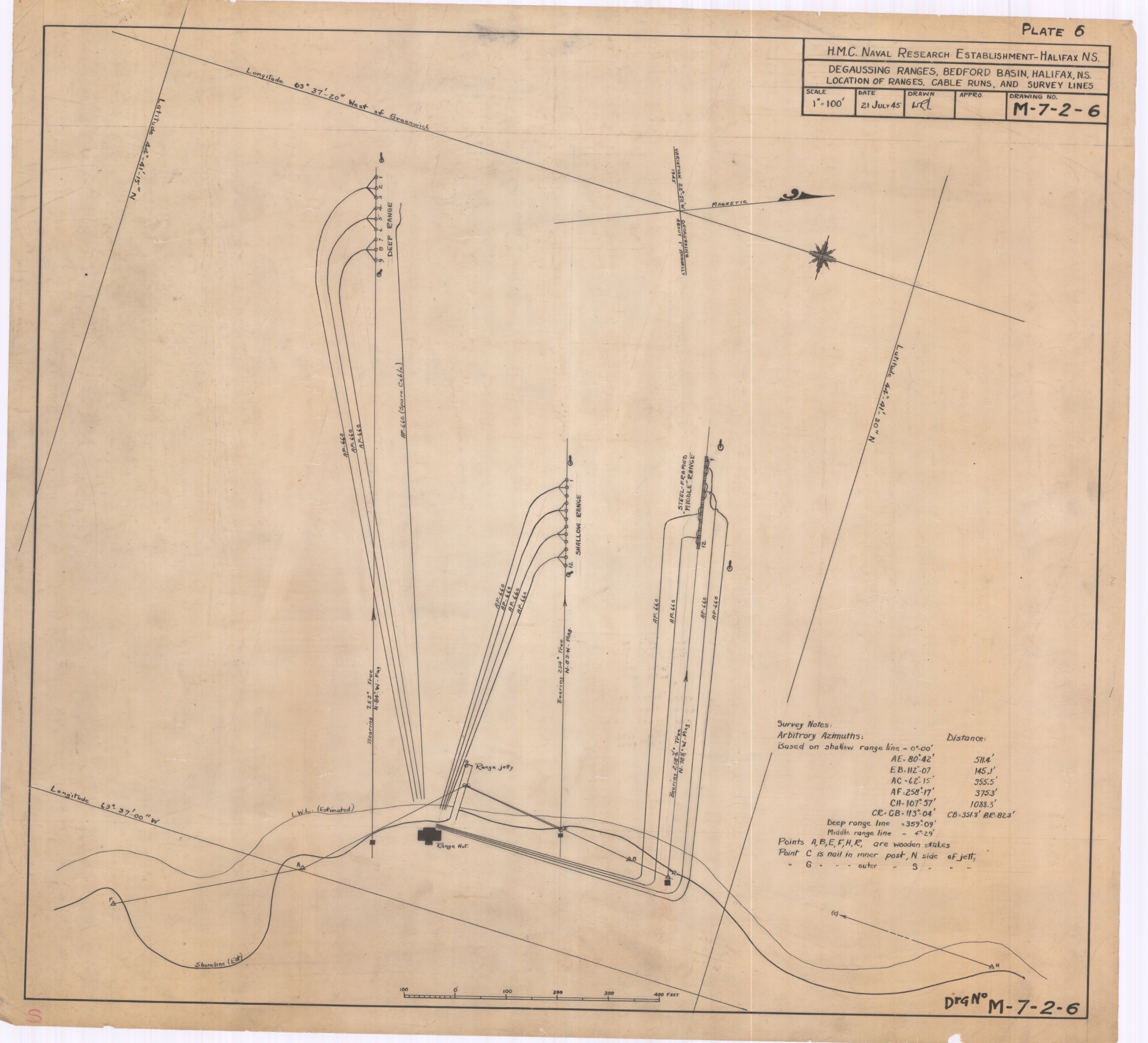

Initially, a magnetometer that had been designed and built in the Dalhousie laboratories was fitted inside a heavy, non-magnetic bronze box that was fitted with handling ropes. The sensor was moved, by hand, along the underside of the ship to measure the magnetic signature. This difficult and labour-intensive procedure earned the nickname of keelhauling. The Admiralty considered an open range to be essential for testing degaussed ships, and approval was given in June, 1940 to begin construction on one. A site was selected, in Bedford Basin, which had a level bottom at the required depths. A pier and building were constructed on an uninhabited portion of the eastern shore of the Basin to facilitate the attending motorboat and shore-based equipment. The facility was put into operation in October of 1940 and the first ship over this original range, the first in North America, was HMCS Arras on November 13, 1940.

The demonstrated utility of the Bedford Range led to the construction of other ranges in Sydney, Vancouver and Quebec City. Writing in 1944, Dr. Henderson recalled that, “The science of degaussing grew up quickly by joint efforts all over the world. Within some two years, it had reached the point where it was not worth putting in any more refinements. The menace of the mine had been reduced practically to a nuisance and the cost of degaussing became the prime factor.” The core scientific staff that had been gathered together in the opening years of the Second World War formed the nucleus of the newly established HMC Naval Research Establishment. This unit exists today as the Atlantic Research Centre of Defence Research and Development Canada. By 1944, the operation of the ranges was considered to be largely routine business and was turned over to non-scientific staff; it continues to be operated today by the skilled staff at Fleet Maintenance Facility Cape Scott.