MWO (RET’D) FLOYD POWDER

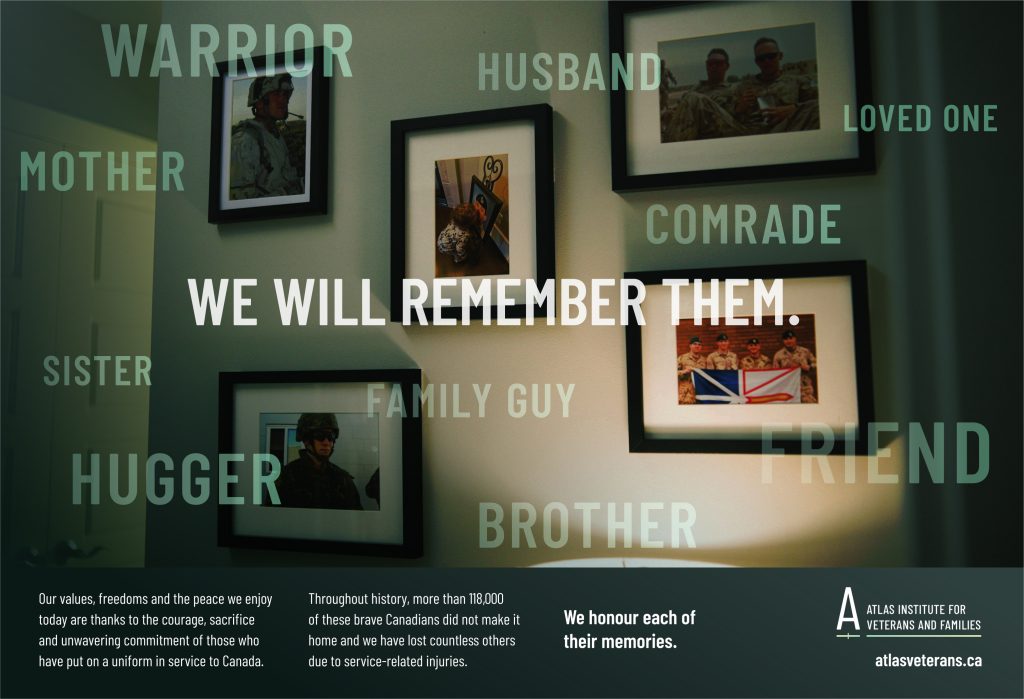

The universality of sacrifice

By Fardous Hosseiny,

President and CEO

The Atlas Institute for Veterans and Families

As Remembrance Day approaches, I find myself pondering a new question this year: “In remembrance, who might be the forgotten?”

Here in Canada we know that more than 118,000 brave soldiers did not return home to their loved ones throughout our short history as a nation. Canada’s eight Books of Remembrance, which record the names of every Canadian who died in service to our country, are currently displayed at Parliament Hill’s Visitor Welcome Centre, in the Room of Remembrance.

Veterans Affairs Canada and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission ensures the maintenance of more than 300,000 markers and grave sites of Canadian Armed Forces members here and around the world, including those whose deaths were not directly attributed to service. It is particularly meaningful to know this exists to maintain those that might have fallen into disrepair or where no living relative remain to continue to provide for the upkeep.

Whether they lie marked in Flanders, Bény-sur-Mer, Beechwood, or unmarked throughout the world, these are places where valour lies. Their lives and their service must be honoured.

Beyond these numbers though there is growing recognition of a number not accounted for — those lost to psychological wounds sustained as a result of service. As conversations become more open and honest about mental health and how this has been a real impact of service, when we lose a former serviceperson (or currently serving member) to suicide, the question many grapple with now is: How do we officially honour those lives?

At the Atlas Institute for Veterans and Families, the feedback we hear from our community is that mental health injuries are no different than the physical injuries which our Veterans incur and should be treated as such. They are no less heroes than those who died in uniform. We can make that statement unequivocally and stand on November 11 with our Veterans and Family members in honouring their loved ones who died both in service and post-service as a result of injuries sustained. It is welcome to see this year’s Memorial Cross Mother (also known as the Silver Cross Mother) recognized for her loss of two sons to the impacts of posttraumatic stress disorder.

As we expand our remembrance practices to include all types of injuries, we have an opportunity to become leaders in advocating for comprehensive recognition of Veterans’ sacrifices and extending these into everyday acts of awareness, support and education around the complex realities of military service.

Perhaps we can move forward with a renewed understanding: Service is service, the blood of all heroes never dies and our remembrance of all should be equally enduring regardless of the nature of their wounds.