TRIDENT ARCHIVE

From the Archives: Torpedoed in the North Atlantic

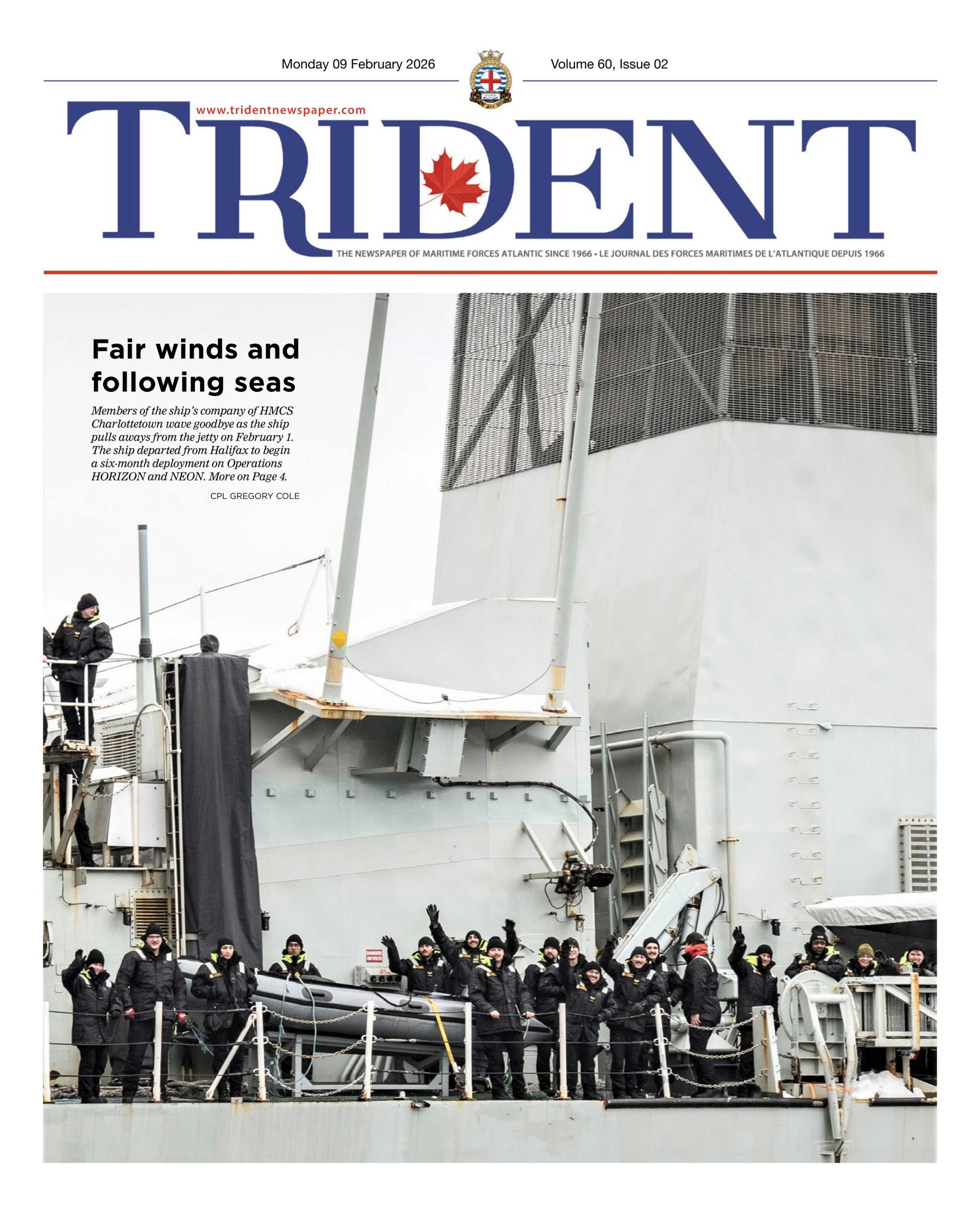

The following is a Trident article written in 1981 by Rear-Admiral Daniel Hanington, a recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross, recounting some of his North Atlantic experiences as a young naval officer during the Second World War, including the sinking of HMS Rajputana.

World War Two broke out in September, 1939, and almost all of us in the 6th Form at RCS (Royal Collegiate School in Rothesay, NB) knew we would be joining up on graduation the next year, though one or two were smart enough to see that the war industry had a profitable future.

The Air Force caught everyone’s imagination in Canada, mine especially after the Battle of Britain began, and I fully intended to offer services to the RCAF until my most respected teacher and friend, George Whalley, joined the Navy and went on loan to the Royal Navy. He promptly proceeded to win the Royal Lifesaving Medal for incredible heroism while rescuing the crew of a sunken destroyer, after which he took part in the last battle against the Bismark and disappeared into the Small Boat section of the Admiralty, where he worked at developing the tiny assault craft used in raids on the French coast. If the Navy was good enough for George, it was good enough for me, so after we graduated in June, 1940, I applied at HMCS Brunswicker and was accepted as a Temporary Midshipman, RCNVR, at the end of July.

Three weeks later I and seven other midshipmen reported to the Naval Barracks in Halifax for a basic course in such things as how to salute and which side of the jacket to do up the buttons on; ten days later we were at sea. Well, not exactly at sea, but in a ship, HMS Rajputana, alongside Pier 21 behind the Nova Scotian Hotel and getting ready to sail for Saint John for a short refit. This would have seemed a tad anticlimactic, but we didn’t have time to think about it.

The Officer-in-Charge of Midshipmen (always referred to as the Snotties’ Nurse) was a fine man by the name of LCdr Dunkley, determined to make naval officers out of us if he killed himself and us in the process, and he nearly succeeded in both. He started us on a regimen that began at 5:20 a.m. with 30 minutes Physical Training, went on to classes in seamanship, gundrill, navigation, engineering, damage control, signaling and anything else he could think of until 4:00 p.m., after which we stood a four-hour watch sometime between then and midnight.

Our spare time was taken up with healthful sports and in writing up our Daily Journals, in which we had to record everything new or important that we had learned during the day, complete with diagrams, and our observations of life in various ports we visited or of unusual happenings at sea.

After a few weeks in Saint John drydock, off we went to where, according to King’s Regulations and Admiralty Instructions, the duties of a naval officer are properly performed – at sea. We were detailed to escort convoys from Halifax across the Atlantic to an ocean meeting point, where they were to be picked up by an escort of destroyers which could protect them against submarine and aircraft attack as they came within range of European bases.

We, as an Armed Merchant Cruiser (AMC), were supposed to defend them against surface raiders in the Western Atlantic; by this time, even we Snotties knew that our armament might just cope with a commercial vessel fitted out as a raider, but would be useless against a pocket battleship or cruiser. Our policy was to attack bravely and gain directions and so mostly escape. Nobody ever said this, but we all knew it; sometimes a battleship would loom up out of the fog on the Grand Banks and, in those few seconds before we exchange recognition signals with HMS Ramillies or whomever, you could just see the Old Man thinking of his posthumous Victoria Cross.

An AMC was a passenger liner converted to a cruiser by installing some guns. They were crewed by a highly mixed bag of retired regular RN officers and Petty Officers, their original merchant marine officers and crew, and Naval Reserve personnel, plus a few of us Volunteer Reserves who had no seagoing experience at all. There was a lot of friction between the three groups; luckily it wasn’t too bad in Rajputana. Anyway, we Canadians were moderately unpopular with all the groups, because we were paid considerably better than the British; as Mids, we got $60 a month, and that was more than a married RN Sub-lieutenant.

TRIDENT ARCHIVE

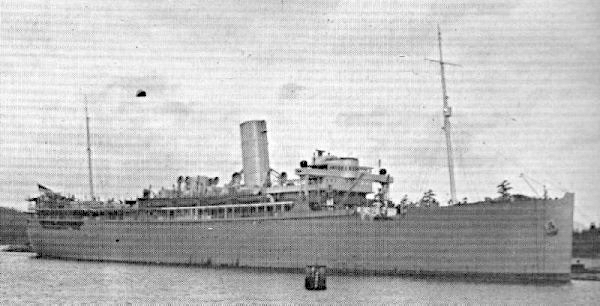

Rajputana was a Peninsular & Oriental (P&O) liner of about 17,000 tons. She had been on the England-Singapore-Australia run; being at the Eastern end when war broke out, she was commandeered by the Admiralty and sent to Esquimalt for conversion to an AMC. There she was fitted with eight six-inch guns built between 1893 and 1901; two three- inch anti-aircraft guns dating from 1914, and eight depth-charges; no sonar, just depth-charges.

She had an optical rangefinder, but no proper fire-control equipment, and of course, no radar, which came in much later. She first went down the South American west coast, where she intercepted a German merchant ship frantically making for home, and in 1940 came through the Panama Canal and up to Halifax for Atlantic Convoy duty.

Though she may not have been much as a fighting ship, from the point of view of amenities she was a floating sin-bin compared to the destroyers and corvettes to which we all went afterwards. Grand piano in the Wardroom, large canvas swimming pool for tropical weather, and even naval modifications couldn’t destroy the comfort of our cabin accommodation. Furthermore, she had kept the entire excellent stock of wine from her liner days, so we Mids, who weren’t allowed spirits, were very lucky.

War at sea had been defined, quite correctly, as 90 percent boredom and 10 percent stark terror. Luckily, there is also a lot of humour, occasionally pretty sick humour, but nonetheless humour. Anyhow, before I get on with the few terrifying events of my war I must tell you of one crucial event in November, 1940, I met Margot! Our Surgeon Commander was a friend of Professor Montgomery at Dalhousie University, whose daughter Shirley was giving what I guess you would call a thé-dansant. Being a good friend, he promptly detailed off four of us Mids to provide a little respectable naval flavour to the proceedings.

We went along to the party, where we found the conversation and the refreshments to be just about as we had expected; neither was very spirited. Margot, who also thought she had better things to do (connected, I believe, with a current boyfriend) arrived late; her mother had bulldozed her into coming on account of some sort of premonition, even phoning Mrs. Montgomery to tell her that Margot would be coming after all, late, which didn’t exactly please that good lady. Well, we danced and we discussed psychology in an amateur sort of way and she had the brightest-sparkling eyes I had ever seen and I never could get her out of my heart thereafter.

Back at sea, the war was still going from bad to worse; the U-Boats were gradually pushing further west as coastal waters got too hot for them. Still, they had not got west of Iceland yet, and back we went on our triangular run from Halifax to mid-ocean to Bermuda and the reverse with convoys. This cycle was interrupted only once, when HMS Jarvis Bay, another AMC, did exactly what she was supposed to do when her convoy was attacked by a pocket battleship. She was sunk in short order, but most of her ducklings escaped. Her captain, Fogerty-Fegan, got a posthumous VC. We, and all other Europe-bound convoys west of the battle, turned around and ran for shelter until the way was clear again.

In April, 1941, we turned over our convoy in mid-ocean and headed for Iceland; there we got orders to patrol the Denmark Strait and intercept a German blockade-runner which was reported to be coming around the north of Iceland to break out into the Atlantic. So we sailed up and down between Iceland and Greenland looking for her, and anticipating no real trouble even if we found her.

On the morning of Sunday, 13th April, just before dawn, as the Navigating Commander, Cdr “Piggy” Paice, was taking a round of stars sights on the bridge with one of us reading the times for him, there was a phenomenal crashing noise on the port side. The ship, and everything in her, stopped dead and she listed about ten degrees to port.

The emergency alarm bells, which were battery operated, started clanging automatically and everyone rushed to their action stations. This wasn’t as simple as it sounds, since everything below decks was in complete darkness and 360 men were fumbling their way towards the guns, the engine room, the magazines, the sick bay and everywhere else they had to go. In my cabin, I scrambled around for my sheepskin coat, found a pair of shoes and headed for the forecastle deck, where I was supposed to take charge of the forward ammunition supply party.

By the time we were more or less organized, dawn was well up, and as we looked around the surface of the sea, flat calm, we could see nothing. Rumour spread that we had struck a floating mine, until suddenly someone yelled “Periscope!” and sure enough about half a mile away to Port we could see the thin feather of an attack periscope having a good look at what he had done. The Port guns were brought to bear, more or less, and four hundred pounds of six-inch shells roared off in the general direction of the U-Boat.

This exercise in killing a gnat with a sledgehammer had no effect, of course, except to make the submarine lower its periscope and start on a slow journey around the ship, having a look from time to time to see if we were sinking yet. We weren’t; the first torpedo had been perfectly placed, hitting us dead in the engine room, filling the place with scalding steam, which killed the watch of Engine Room Artificers and Stokers, and cutting off all steam to the engines and the electrical generators. However, the watertight doors and the bulkheads held firm, and we were in no danger of sinking.

TRIDENT ARCHIVE

For the next two hours we divided our time between firing one gun a minute at the sea (more if the periscope briefly appeared), getting more warm clothing because the air temperature was only 32°F, having a sandwich and worrying what was going to happen next. And making sure that the lifeboats, which could each hold 60 men, were turned out and ready to go.

Eventually the U-Boat captain decided that this wasn’t good enough, and fired at us again from the starboard side from a range of less than half a mile. There was something wrong with the depth-keeping gear on that fish, because it ran all the way on the surface. I want you to know that wherever you may be standing along a 600 foot length of deck, you are positive that any torpedo running on the surface is heading directly for you; I was, and as I was standing directly on top of a magazine con-taining some twenty tons of gun cotton, I was perturbed. If they ever salvage the Raj, I guarantee that they will find my handprints on the rail around that magazine hatch.

The shot was another beautiful one; the torpedo struck just a little further aft than the first and blew out the bulkhead between the aft end of the engine room and No. 3 Hold. The ship was now open to the sea for nearly half her length, and she clearly could not stay afloat for long.

All this time, other things were happening. At the first explosion, “Piggy”, who was only halfway through his round of sights, also exploded “That’s ruined my sights!” He then threw his sextant on the deck and stamped on it. He was a navigator of the old school, nothing was more important than his sights. While I was pondering life on top of the magazine, somebody got into my cabin and stole my camera. My friend and fellow Mid, Murray Cook, was laid low in a cabin on the starboard side with a nasty case of measles; after the second explosion he looked up as soon as his teeth stopped rattling to find that the ships side had been rolled back like a sardine can top and he had an unobstructed view of the ocean. He arose in some haste and proceeded to the upper deck, where I met him. Would you believe it, there was not a single spot left on him. Most dramatic cure for measles I ever saw.

By the grace of God and the forethought of the Admiralty, there was a battery-powered emergency radio transmitter in the radio room, and our Chief Telegraphist was up there all this time broadcasting the naval equivalent of an SOS. And the barrels were floating out of the hole on the starboard side. The empty holds of the AMC’s had all been filled with empty 50-gallon oil drums, presumably in hopes of limiting the amount of water that would enter. in circumstances like ours, though it was rumored that the designers calculated that, instead of sinking, she would rise a foot if torpedoed. This was too much for the gun crew on Y-gun deck, who started lustily singing the Beer Barrel Polka, “Roll out the barrel, we’ll have a barrel of fun!”

By now, we were devoting serious attention to getting away from the ship, which had begun to settle by the stern. The sea was still calm, and there was a lot of thick black fuel oil on the water, making it even flatter. The boats, except for one that had been destroyed by the second explosion, were manned and then lowered away by a few men left aboard for the purpose. Unfortunately, one of them caught on a projection on the starboard side (remember the ship was listing to port) and turned over, dumping 60 men 30 or 40 feet into the oil, then broke loose and fell on them. This permanently discouraged many, and produced most of our 42 deaths, though some died later from getting oil in their lungs. The boats, which were really overcrowded with 60 men, spent some time rescuing those in the water who could not be left there long in 42° F.

Poor “Piggy” didn’t make it; he seemed to suffer heart failure, and just slid off the bottom of the upturned lifeboat and disappeared. Another who disappeared was a Mid, Frank Johnson, who joined up with me in Saint John; that really hurt. He seemed to have been badly dazed by the second explosion, and it was said that he had last been seen climbing up the ladder on the funnel; there could have been no good reason for that.

At this point the wind began to blow and the sea to make up, so that we were getting colder and wetter. The Raj slowly sank her stern beneath the sea and reared up her bow till she was straight up and down, then she sort of sighed and slid under. There was a long silence; I had a big lump in my throat, as well as a lot of sea down the back of my neck. Then we turned the boats in the general direction of Iceland and started rowing.

The weather was rapidly deteriorating; it wasn’t so bad for us who were rowing, but the injured who had been picked out of the water were rapidly freezing solid and we had to give them much of our warm clothing. I was mournfully pondering the fate of my friend, the Chief Gunner’s Mate, who had laden himself with valuable stores, like pistols and stop-watches, for which he was responsible and naturally gone straight to the bottom on jumping in, when suddenly a droning noise was heard from the southeast and there was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen, even more so than Margot. An RAF Sunderland flying-boat rumbled overhead, waggling its wings; Iceland had heard our SOS and sent it to look for us. Not long after, two destroyers appeared from the same direction, one Polish and one British, the Matchless.

Matchless stopped and picked us up; since the sea was now pretty rough, she lowered cargo netting down her sides and we had to wait till the boat was on top of a wave and then make a desperate leap as high on the net as we could get before the next wave lift-ed the boat again and knocked us off. The men were taken up to the mess decks, and the officers to the Wardroom, where we were registered, deprived of our sidearms, given a cigarette and a tumbler full of brandy and led off to somebody’s bunk to sleep. I suppose we were given a meal as well; I can’t remember it.

The ships headed for Reykjavik. We arrived there the next morning and spent several days there. We were put into an old accommodation ship; the only thing I remember about her was that every meal consisted of some form of mutton and potatoes. However, the Supply Officer had got off the ship with all his cash intact, so we each got a small casual payment, or advance, and were able to go into town and buy Danish pastries and other goodies. While there we discovered the Telegraph Office, so several of us sent cables home to say we were alright. Mine said only “Sunk, saturated, saved. Love, Dan.”