NAVAL MUSEUM OF MANITOBA

One ship’s story: HMCS Spikenard and her connection with the Crow’s Nest

By CPO1 (ret’d) Patrick Devenish,

CNMT

During the War years 1939 – 1945, the Canadian Shipbuilding Industry completed four destroyers, 70 frigates, 123 corvettes, 122 minesweepers, 398 merchant vessels and over 3600 specialized vessels (LSTs, MTBs etc). Of the 123 corvettes produced, 107 of these saw active service with the fledgling Royal Canadian Navy. This is the story of one of those corvettes.

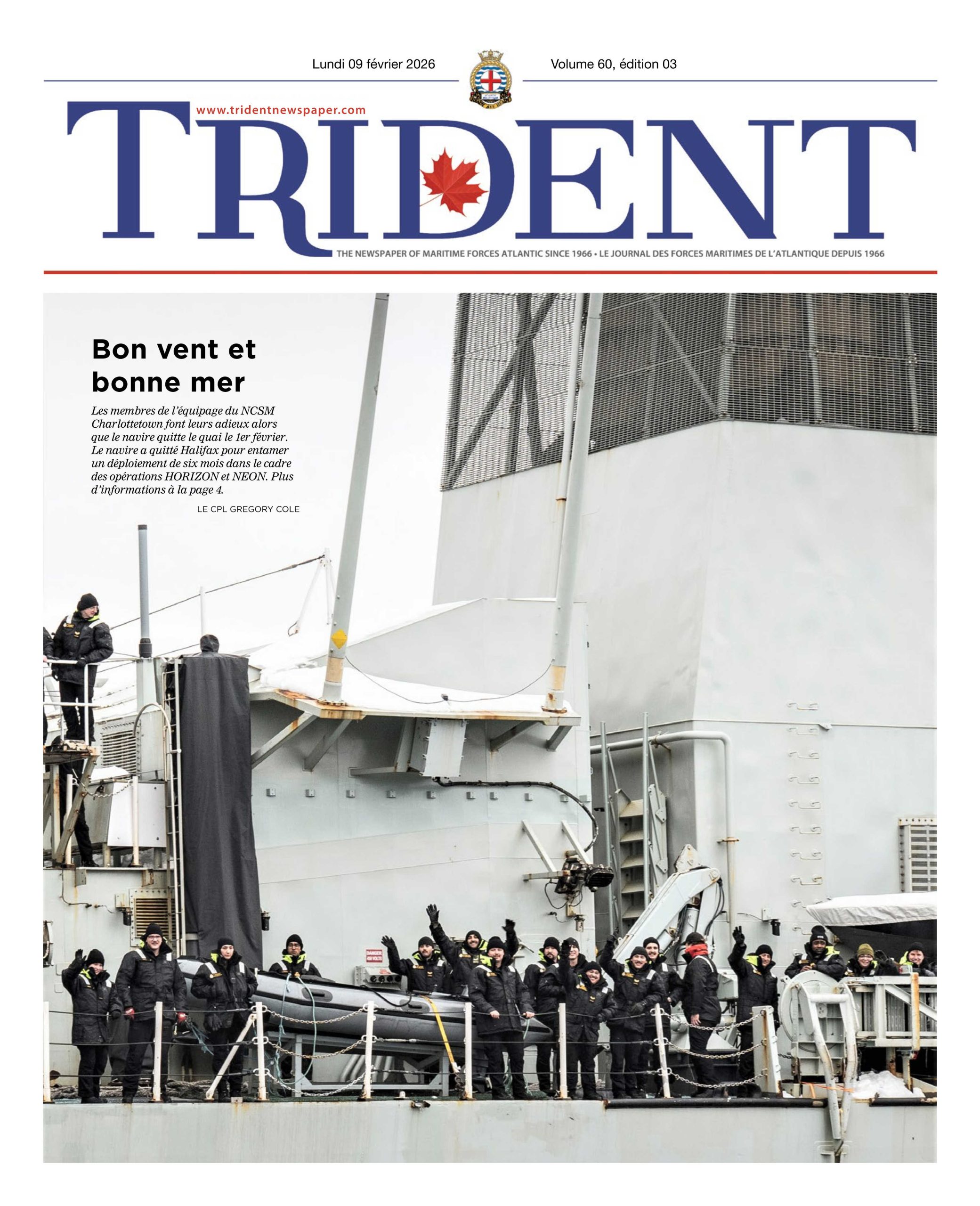

Le NCSM Spikenard, originally built for the Royal Navy (carrying the Flower name assigned to the class), was eventually turned over as an RCN asset. Her career, though short, is one of those amazing tales of wonderment which would lead to a unique relationship between two cities, thousands of miles apart, well over six decades later.

Launched from Davie Shipbuilding Company Limited in Lauzon, Quebec on December 6,1940, HMCS Spikenard was one of 10 of the original batch of 64 corvettes built in Canadian shipyards for Royal Navy use. Delivered to British ports in January 1941, the Canadian steaming crews suddenly became the ships’ operational crews as the Royal Navy found themselves woefully short of personnel. HMCS Spikenard was worked up out of Greenock, Scotland and quickly transferred to the 4. Escort Group operated out of Reykjavik, Iceland. After completing three convoy runs to Iceland, Spikenard was transferred to the Newfoundland Escort Force. A new system developed by the RN and RCN was to see Canadian vessels escort slow convoys (designated by the SC prefix) from Sydney, Nova Scotia to a mid-ocean point where the escort duties would be turned over to the Royal Navy with a final destination of Londonderry, Northern Ireland.

With the fleet based out of St. John’s, Newfoundland, the first of these Newfie-Derry convoys, SC-67, comprising 22 merchantmen, departed Sydney on February 2,1942 picking up their escort out of St. John’s late in the day. With the 22 merchantmen arranged in a rectangle of seven columns three or four ships deep, the escorts were arranged with Spikenard (Senior ship; CO – LCdr Shadforth) well ahead of the starboard column, with Louisbourg approximately 2000 yards astern. Three miles back, Dauphin kept station well behind the convoy to the starboard side while the same arrangement was mirrored down the port side with Chilliwack in the lead position followed by Lethbridge and finally Shediac trailing astern of the convoy with Dauphin.

This, February 10, was the last night of their escort duties and the convoy was to be turned over to a Royal Navy escort the following morning. At around 2230 hours on that dark, windy, moonless night however, fate would deal a lethal blow as three explosions in rapid succession lit up the sky. The convoy had sailed into two German U-boats that had been lying in waiting: U-591 et U-136. Immediately it is ascertained that the Norwegian tanker Heina in the extreme starboard column was hit and though the second and third explosions could not be pinpointed, all escorts made hard turns to head up the torpedo tracks in an attempt to track the U-boats on their asdic. Unbeknownst to the crews of the other five escorts, Spikenard had been hit between her bridge and foc’s’le; so severe was the damage that she sank beneath the waves within five minutes.

Not wanting to give away their positions, none of the ships risked a wireless signal, which would allow one of the U-boats to zero in on the sender’s position. It is not until the early light of the morning of February 11 that the escort group realized Spikenard was no longer with them. This, in itself caused no immediate concern as it was quite possible she had raced ahead to contact the waiting Royal Navy escort to assist in hunting the U-boats.

Unfortunately, when the convoy reached their waiting Royal Navy escort, Spikenard was nowhere to be seen. The Royal Navy corvette HMS Gentian was detached to race down the convoy’s track and late in the afternoon of 11 February, her lookouts sighted a carley float with just eight survivors clinging to life. (Originally, the liferaft held 10 people but two succumbed to the cold and injuries and were committed to the sea.) These eight were landed when the ship reached Liverpool, England. In all, 57 of Spikenard’s crew were lost including her beloved Captain, LCdr Hubert C Shadforth.

U-136, the submarine subsequently credited with Spikenard’s sinking continued to wreak havoc on the Atlantic convoys sending three more merchantmen as well as the Canadian fishing schooner Mildred Pauline to the bottom. Her end would come though just four months later, when she was sunk, with all hands, by a combined French Navy-Royal Navy Force, off the Canary Islands.

A unique memento of Spikenard still exists in the Crow’s Nest Officers’ Club in St. Johns, NL to this day. Established in 1942 by Commodore Murray, the Seagoing Officers’ Club was a place for ships’ officers to gather close to the waterfront, and therefore close to their ships.

The evening prior to Spikenard’s group’s departure, the officers gathered for some well wishing in the club even though it was not yet complete. At a makeshift bar, a challenge was levied to see who could drive a 6” nail into the hard pine floor with the least number of blows. Reportedly the winner, LCdr Shadforth’s spike was subsequently ringed in brass in the floor when he failed to return. Removed during renovations following the war, his spike, engraved “SPIKENARDS SPIKE” adorns a special place on a pillar purported to be a few feet from where ‘Bert’ Shadforth had driven it into the floor. Each year, the cities of St. John’s, Newfoundland and Londonderry, Northern Ireland honour all Atlantic escort crews with a celebration coinciding with the anniversary of the loss of HMCS Spikenard.

The Battle of the Atlantic would rage on for over three more years, culminating, for the city of St. John’s, anyway, with the surrender of U-190 in Bays Bull Newfoundland on 11 May 1945. Still intact at the Crow’s Nest, among other U-190 artifacts, is the submarine’s logbook tracing her last weeks of wartime action.

Footnote:

Downsizing following the First World War, The War to end all Wars, meant that the brand new RCN along with her sister services was ill-prepared for war, a war which would turn out to be of a magnitude unprecedented.

The story of Canada’s fledging Navy is told in other archives in much more detail but here, in a condensed form, is a story not often heard.

In 1939, as the clouds of war closed, Canada’s contribution to the war at sea was little more than a token gesture. Fewer than 4000 personnel and seven semi sea-worthy vessels constituted the Royal Canadian Navy. Immediately upon commencement of hostilities on September 3, 1939, the RCN’s primary duty became guarding the North Atlantic convoys. With the US still out of the war and Britain dependent entirely on her colonies for supplies, the port of Halifax and the RCN suddenly became paramount. From an antiquated force, the RCN grew to over 350 surface combat vessels and by war’s end, the RCN would be the third largest Allied Navy in excess of 100,000 personnel.

The RCN contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic was 29 German U-boats sunk and 15 probables. Though some post-war records leave many unknowns, discovered sunken ships and submarines continue to reveal the truth. Records from the German Navy indicate the typical RCN sailor to be an admirable yet formidable foe.

Over 2000 RCN sailors paid the ultimate sacrifice in the Second World War. In faraway lands and in the depths of the eternal seas, they lie. For them, we weep; for them, we rejoice.

Bibliography:

Bishop, Arthur: True Canadian Heroes at Sea, Toronto ON, Key Porter Books Limited, 2006.

Burgess, John and MacPherson, Ken: The Ships of Canada’s Naval Forces, 1910-1981, St Catherines ON, Vanwell Publishing, 1983.

Darlington, Robert and McKee, Fraser: The Canadian Naval Chronicle 1939-1945, St Catherine’s ON, Vanwell Publishing, 1996.

Lamb, James B.: The Corvette Navy (True Stories from Canada’s Atlantic War), Toronto ON, Stoddart Publishing Co. Limited, 2000.

MacPherson, Ken and Milner, Mark: Corvettes of the Royal Canadian Navy 1939-1945, St Catherine’s ON, Vanwell Publishing, 2002.

http://www.navalhistory.ca